LGBT+ Art Histories

Simeon Solomon, detail of Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene, 1864, watercolour on paper, 33 × 38.1 cm, Tate, London (Image: Tate)

It is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, and we wanted to celebrate by asking six art historians from the LGBT+ community to choose one of their favourite pre-20th-century artistic representations of queer love and experience. Here is what they chose…

You can read the in-depth extended version here.

Baylee Woodley: The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham, 1480

This memorial brass commemorates an evidently intimate relationship between two women, Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge, who were buried together in Etchingham Parish. The inscription along the bottom requests God’s mercy for them both. Elizabeth is shown on the left with her hair down and she is quite a bit smaller than Agnes. This likely symbolizes her being both unwed and young when she died in 1452 in her mid-twenties. Agnes is shown on the right and (although she too seems to have remained unwed) she is shown as a more mature woman. This is likely because she was in her fifties when she died in 1480. Significantly, this brass is designed in the style of memorial brasses for married couples, but with additional intimacy: unlike other brasses from this time, Agnes and Elizabeth look into each others’ eyes. It was unusual for Agnes to be buried with Elizabeth instead of in the Oxenbridge mausoleum, so both of their families must have agreed for it to have happened. The initial request for the site of burial most likely came from the (now lost) will of Agnes herself.

I remember how meaningful it was to read Judith Bennett’s chapter on this brass in The Lesbian Premodern (2011) when I just beginning to ask whether or not queer art histories were out there. This answer is, of course, yes! They are everywhere! But this was not always as common sense to me as it is today, so this brass reminds me why I want to keep sharing queer art histories with others.

Read more about why I chose this brass here.

Baylee Woodley is a PhD student at the University College London and the current curator of Queer Art History. This educational resource and archive of queer art and culture was created by transgender activist, artist, and Point Foundation scholar Casey Hoke in 2017.

Unknown artist, The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham, c. 1480, brass, Etchingham Parish, Sussex (Image: Wikipedia)

Queen Njinga Mbandi (Anna de Sousa Nzinga), by Achille Devéria, printed by François Le Villain, after Unknown artist, hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s, 48.8 x 35.8 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London (Image: NPG)

Bi History: Ngola Nzinga Mbandi, hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s

This hand-coloured lithograph, housed in the National Portrait Gallery in London, was printed in the 1830s by François Le Villain, and depicts the sixteenth-century leader of Ndongo and Matamba, Ngola Nzinga Mbandi. Born in the early 1580s to the ruling family of the Kingdom of Ndongo (what is now Angola), Nzinga Mbandi became leader after her brother’s death in 1626. Despite being deposed by Portuguese colonists, Njinga Mbandi fought for the independence of her kingdom over the course of her 37 year reign. She used her political skills and military strategy to gain alliances and to resist the expansion of the slave trade (she offered refuge to people who escaped enslavement). Njinga Mbandi ultimately transformed her Kingdom into a commercial state to rival Portuguese colonies.

Njinga Mbandi used the honorific Ngola, which can be translated to mean king, and dressed in traditionally male clothing. Her relationships with people of all genders have been subject to much speculation, including having a large number of ‘chibados’ in her court - a group of gender non-conforming people who dressed outside defined gender roles and had relationships which were viewed as homosexual by colonial eyes. In their book ‘Boy-Wives and Female Husbands: Studies in African Homosexualities’, Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe remind us that Njinga Mbandi’s court organisation “was not some personal idiosyncrasy but was based on beliefs that recognized gender as situational and symbolic as much as a personal, innate characteristic of the individual”. Notably, in this lithograph, Nzinga Mbandi’s non-gender conformity is completely overlooked: her breast, rosy cheeks, red lips and earrings all cast her in relation to 19th-century European ideals of feminine beauty (her name is also presented in its European state, Ann Zingha).

Learn more about this artwork here.

Bi History is an Instagram account that explores the history of bisexuality and highlights the role of bisexual+ activists in LGBTQ+ history.

Dan Vo: The Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough (1770)

To mark LGBT+ History Month I have chosen The Blue Boy (1770) by Thomas Gainsborough. It was partly to mark the happy occasion of his return to the collection after spending one hundred years in The Huntington (the painting was sold at auction in 1922). In the 18th century when Blue Boy was painted, it exemplified a culture of 'sensibility' in Britain that demonstrated enlightened values and refinement. However, some feared it was a step away from masculinity. David Garrick, a friend of Gainsborough's, suggested it had elements in common with the dandy or molly of Georgian London. Many would follow who would draw attention to the queer properties of Blue Boy, with a long lineage of queer folk who have reworked the image in their vision over the years.

For example, the painting was subverted in the 1974 premiere issue of Blueboy, a gay men’s magazine, named after the painting. Here, a handsome athlete stands in. Although he has removed his breeches, the feathered hat has shifted to hide his modesty. The pastoral setting is made seductive. The cover even features a risqué graphic design of a double ‘b’ hinting at a rather ambitious phallus. The bemused model holds our gaze knowingly. An advert inside proclaimed a brotherhood of ‘The Blue Boy’ that is, “suave, cultured, sophisticated, discrete, sincere... a philosophy that Gainsborough’s 'Blue Boy' expresses so very clearly to the discerning.” Discrete seems antithetical given the large 24-carat gold medallion with a Cloisonné figure of Blue Boy affixed, offered for sale so men could broadcast their proclivities via their camp accessories.

To see the cover which the archivist of Blueboy magazine, Miss Kitty, kindly recovered for us along with another contemporary spin on Blue Boy by queer visual artist Kehinde Wiley (who currently has an exhibition at the gallery), you can read my full article written recently for the National Gallery here.

Dan Vo (@DanNouveau) is a Patron of LGBT+ History Month as well as Project Manager of the Queer Heritage and Collections Network. The network which assists galleries, libraries, archives and museums in their research on queer art history. Additionally, he is Marketing Manager at Queer Britain, the first LGBTQ+ museum in the UK due to open in Spring 2022.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy, 1770, oil on canvas, 177.8 x 112.1 cm, Huntington Art Museum, California (Image: Wikipedia)

Loïc Desplanques: Achilles Mourning Patroclus by John Flaxman, 1793

John Flaxman, Achilles Mourning Patroclus, 1793, engraving, 18.9 x 28.4 cm, British Museum, London (Image: British Museum)

This engraving was made in 1793 by British sculptor and draughtsman John Flaxman. The scene depicts the ancient Greek hero Achilles lying next to the lifeless body of his lover Patroclus, who has just been killed in battle. The exact nature of the relationship between the two Greek warriors has been debated for centuries, but several sources dating back to ancient Greece assume without question that they were sexual and romantic partners. Although, in some circumstances, sexual and romantic relationships between men were permitted in ancient Greece, in general they were meant to be abandoned in time for the male duty of marrying and fathering children. Notice how in Flaxman’s engraving, Achilles’ mother Thetis arrives to the left, bearing newly forged armour for her son; urging him to turn away from his grief and deceased lover, to return to war and fulfil his social role of hero and warrior. It is not just the weight of his sorrow that bears down on Achilles, but also the expectations of his mother, the gods, fate, and society. Much like the more modern trope, where queer relationships are permissible in fiction or film only as long as the stories end tragically, this love had a mandatory expiration date.

Flaxman introduces a surprisingly tender tone in this engraving: it is an intimate portrait of two lovers, embracing softly in bed, almost as if they were both living and simply at rest. His bold use of white space seems to emphasise the sense of loss and isolation felt by the grieving Achilles. Flaxman’s depiction of Achilles’ mother Thetis also merits close attention. In contrast to other contemporary depictions which show her boldly and impatiently calling her son back to war, here she bows her head in respect and averts her gaze. This sympathy in her posture reverberates in Flaxman’s own empathetic artistic style. Like Thetis, both the artist and the viewer are intruding upon a private, painful scene; the last minutes of a doomed love between two men.

Read my in-depth view of the engraving here.

Loïc Desplanques is a writer and art historian based in London, with a particular interest in the male body in nineteenth-century European art. He runs the Instagram account @_beau.ideal_ which explores the male body in the history of art.

Esme Garlake: Self-Portrait by Marie Laurencin, 1906

The French painter and printmaker Marie Laurencin is primarily associated with the Parisian avant-garde in the early decades of the 20th-century; as one of the few female Cubist painters, her work explores images of femininity and depictions of women in her characteristic grey-pink tones. Laurencin had romantic relationships with both men and women, including the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire and the American writer Natalie Clifford Barney.

Although many of Laurencin’s paintings depict pairs or groups of women, I have chosen to look at a simple pencil self-portrait drawn by the artist in 1906. The loose, sketchy style shows a self-confidence that is reflected in her direct gaze (since it is a self-portrait, this confidence is directed first towards herself, and then towards the viewer). The way that Laurencin depicts herself with her head tilted slightly to one side gives an informal tone, as if she is inviting us into her world. It is a record of a moment when Laurencin as an artist is exploring how she sees herself. The knowledge that she was queer (to use today’s term) reminds me that whatever I am doing, however I present myself or whomever is in my life, whether or not I am draped in a rainbow flag, my queerness remains just as valid and real.

Read more about why I chose this self-portrait here.

Esme Garlake is an art historian and writer based in London. She specialises in ecological approaches to pre-20th-century art, particularly in early modern Italy.

Marie Laurencin, Self-Portrait, 1906, pencil on paper, 34.9 x 31.1 cm, MoMA, New York (Image: MoMA)

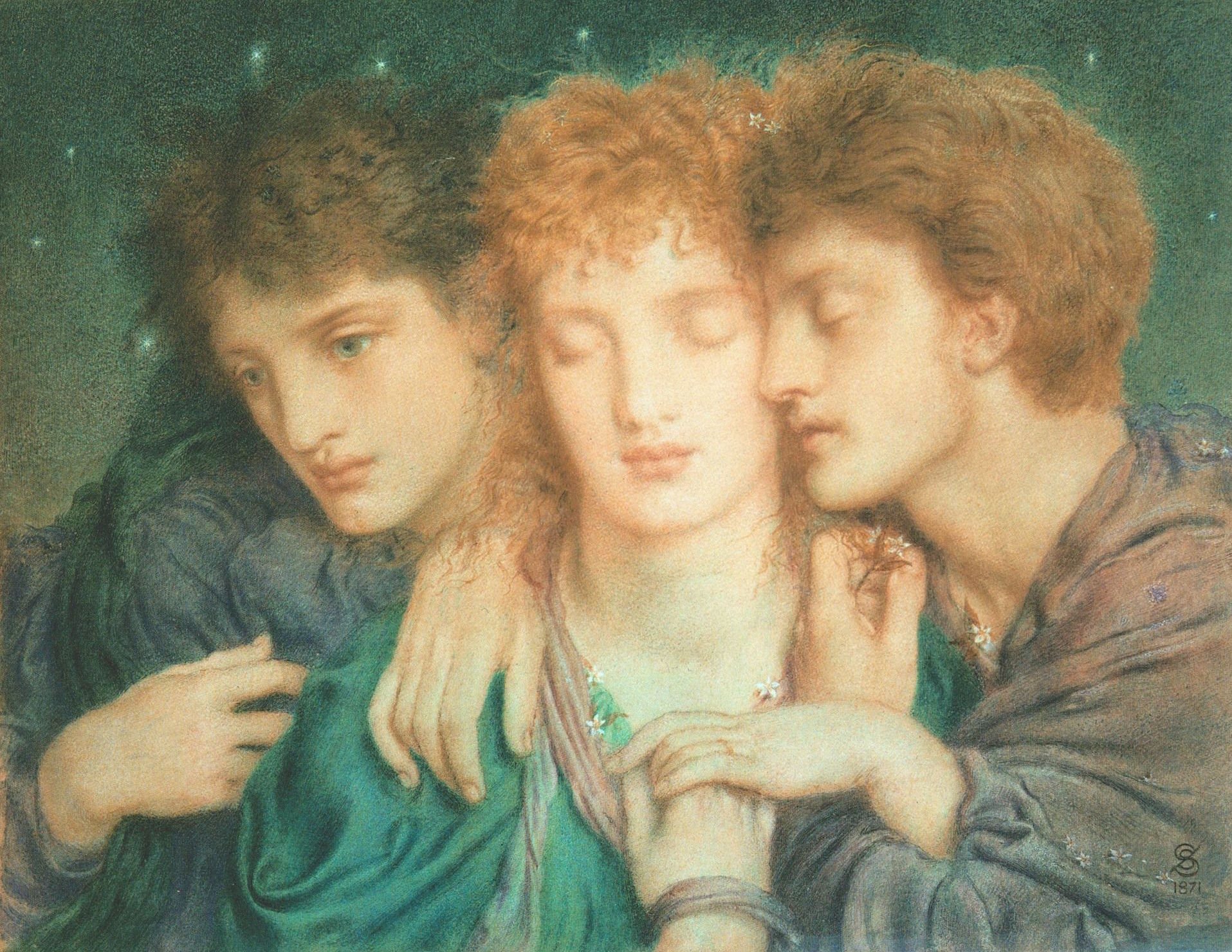

Alice Dodds: The Sleepers and the One that Watcheth by Simeon Solomon, 1870

Simeon Solomon, The Sleepers and the One that Watcheth, 1870 (Image: Pinterest)

In 1873 and 1874, Simeon Solomon was arrested for his relationships with men and, as a result, fell from his position of the ‘darling of the Pre Raphaelites’ into poverty, loneliness and alcoholism. Painted three years earlier, Solomon’s The Sleepers and the One that Watcheth holds an atmosphere of desire, longing, hope and uncertainty that, in my view, movingly raises the question of how to navigate the tensions and complexities around queer desire.

In this painting, three androgynous figures are intertwined - but two more intimately, leaving the third figure as the Other that ‘watcheth’. The third figure’s vacant gaze and melancholy expression seems to reflect an unsettled longing, as if turning the gaze inward. The exact dynamic between the trio is hard to determine. Since the ‘Sleepers’ seem to fit into more normative depictions of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ figures, do they represent distance from the third figure? Does the more ‘feminine’ figure in the middle of the scene divide the longing ‘one that watcheth’ from the affections of the more ‘masculine’ figure to the right? Or are the more ‘feminine’ figure’s wider affections prevented by the arm wrapped protectively around her? The ambiguity of their relationship leaves the image open to, perhaps, a universal queer reading that resists definition. Ultimately, the figures are simultaneously entangled and divided, affectionate and awaiting affection. They are bisexuality, polyamory, unrequited lesbianism and legally-forbidden homosexuality all rolled into one complex relationship. It is an image that is compellingly intriguing and I find still relevant today in its embrace of the complex and often undefinable experiences we face today as queer people.

You can read more here.

Alice Dodds @theyoungarthistorian is a student at The Courtauld Institute interested in craft, gender and sexuality in the long nineteenth century -- which you can find her talking about constantly on TikTok.

read more about each piece in the extended version here

February 2022