Luxury and Power: July Pick of the Month

The quite literally dazzling Luxury and Power: Persia to Greece exhibition is currently on display at the British Museum. The exhibition explores the use of luxurious artefacts as symbols of power that transcended the borders of the Persian Empire from 550-30BC. This month, we wanted to delve into the decadent display of ancient artefacts on show. Here are our top 5 objects from the exhibition.

1. This gold armlet was discovered in Takh-i Kuwad in Tajikistan, and is part of the Oxus Treasure. In total, the treasure consisted of 180 gold and silver artefacts and 200 coins. Crafted by Achaemenid Persian artisans in the 5th-4th centuries BC, the metalwork showcases the incredible skill and opulence of the Persian Empire. The terminals of the armlet are mythological animals; leaping lion-griffins. The intricate ‘honey-comb’ gaps of their bodies are the reminder of the lost cloisonné work - a popular style of metalworking across history, where coloured faience, glass, and stone were inlaid, to give a polychromatic look.

Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

2. This millefiori bowl was created in the Hellenistic period, between 225-200 BC, in Cyprus. Discovered in a chamber tomb in Canosa di Puglia, the bowl is an exquisite specimen of the ‘thousand flower’ or ‘mosaic’ technique. The method was so complex, that even today we are unsure of the precise steps undertaken. Layered glass canes were thinly sliced and melted together under high temperatures in moulds to be shaped into a vessel. Materials used in this particular bowl included glass in shades of cobalt blue, yellow, white, and clear glass encasing gold leaf.

Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

3. This gleaming silver and gold artefact is a rhyton. These were the archetypal Persian drinking vessels. Wine was poured into the top and was dispensed from a small opening at the base. This hole was held closed by one's finger until the horn was lifted above their mouths, ready for consumption. Unearthed at Altintepe in Turkey, this rython was made by Achaemenid craftsmen between 500-400 BC. Animals and mythological creatures were popular choices to adorn drinking horns, with this one showing the forepart of a winged griffin. Around its neck, formerly was a jewel pendant, at some point either purposefully removed or lost.

Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

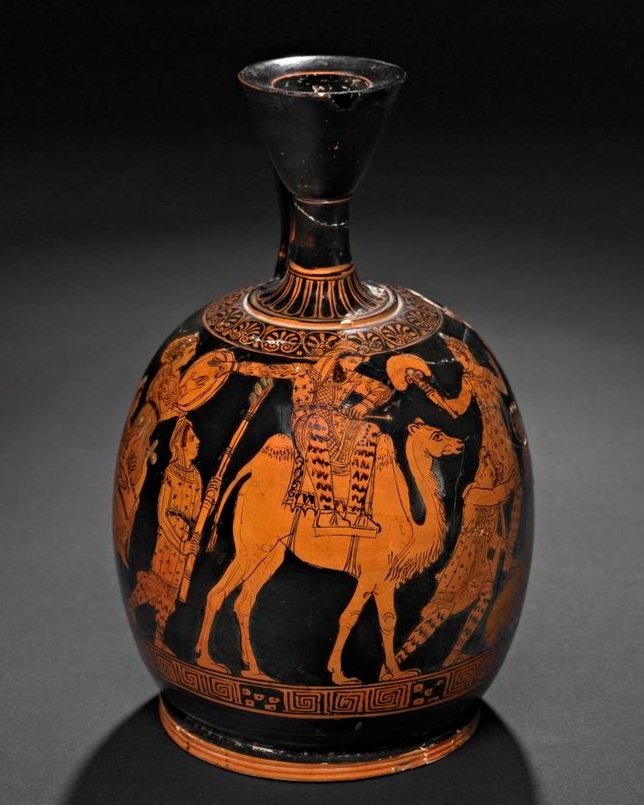

4. A favourite artefact of Professor Lloyd Lewellyn-Jones is this red-figure lekythos from Basilicata, in Italy. Used to store perfumed oil, the flask was manufactured in Athens, Greece, between 410-400 BC. The scene shown is debated by scholars. One interpretation is that it depicts a Persian procession, with the King dressed in all his finery, riding a Bactrian camel. Surrounding him are performers ranging from dancers to musicians. The Ancient Greeks were intrigued with Persian traditions, such as the Achaemenid court travelling across the Empire, between capital cities, each year. Therefore, this imagery on Greek artefacts shows the exotification of the Persians.

Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum

5. The exhibition features a number of loans from museums around the globe. The most striking of these is the Panagyurishte Treasure loaned by the National Museum of History in Sofia, Bulgaria. The set consists of nine almost pure gold objects, totalling a weight of over 6kg. The ornate drinking vessels were discovered in 1949 by three brothers digging for clay. Dating to 300 BC, the group likely belonged to a Thracian ruler, used for ritual or banqueting purposes. The three jugs take the form of women, potentially the Greek goddesses Athena, as shown with a helmet, Aphrodite, and Hera. Conversely, they may represent the legendary warriors, the Amazons, who inhabited the Black Sea coastline. They reflect the overlapping of Greek, Persian, and indigenous Thracian artistic and cultural practices.

Image: © Todor Dimitrov, National Museum of History, Bulgaria

The exhibition is running until 13th August 2023, tickets are available here.

(Written by Han Parker on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, July 2023)