Giovanna Garzoni: May Pick of the Month

There are currently a range of exhibitions dedicated to long-overlooked women artists from pre-modern art history, ranging from Berthe Morisot at Dulwich Picture Gallery and Evelyn De Morgan at Leighton House in London, to a major upcoming exhibition (opening on 6 May) devoted to Lavinia Fontana at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. For our Pick of the Month this May, we thought we would highlight the work of another brilliant woman artist: Giovanna Garzoni. We have also published a video version of this article on our YouTube channel.

Who was Giovanna Garzoni? Garzoni one of the most accomplished botanical artists in the 17th-century, and a pioneer in the still-life genre. At the peak of her career, her artworks were so well received by the public that she was able to ask any price for them. Today, there is a renewed interest in Garzoni’s life and works; she was the subject of an acclaimed exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery in 2020.

Childhood and artistic training

Garzoni was born in 1600 in the Marche region of Italy, into a family of Venetian origin. Although little is known for sure about Garzoni’s artistic training, it is likely that she studied as an apprentice with her uncle, who was a painter. Like many women artists at the time, she received an elite education in music, literature and art, which would later allow her to enter the highest courts in Europe.

Garzoni grew up in Rome, and it was there that she had her first commission (that we know of) in 1616, when a chemist commissioned her to paint a herbarium (a collection of dried plant specimens that are stored, catalogued and studied). In the early 17th-century Europe, the expansion of trade and exploration beyond Europe, as well as scientific and technological developments such as the invention of the microscope, meant that distinctions between art and natural history were blurred. Garzoni’s ability to meticulously depict botanical subject-matters would therefore make her hugely popular with courts and scientific academies in many European cities.

Dr Sheila Barker, curator of the 2020 exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery, reflects on Garzoni’s art: “She evinced a real curiosity and a real affinity for novel things, and new things, and strange things, and she didn’t segregate them into a kind of cold world of display. In her art, and in her life, she was trying to understand her place in relation to the rest of this big, fascinating world that people were in the process of discovering.”

Early career

Between around 1618 and 1620, Garzoni visited the Medici court in Florence (where she probably met Artemisia Gentileschi, another female painter). Here is an early self-portrait, made when Garzoni was between 18-20 years old. She represents herself as a Muse or as an androgynous Apollo, holding a stringed viol with a laurel wreath on her head. 16th-century women artists in Italy such as Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana had developed a new type of portrait genre, depicting the woman artist with a musical instrument. Garzoni is clearly participating in this genre, showing off her artistic skills and her elite education.

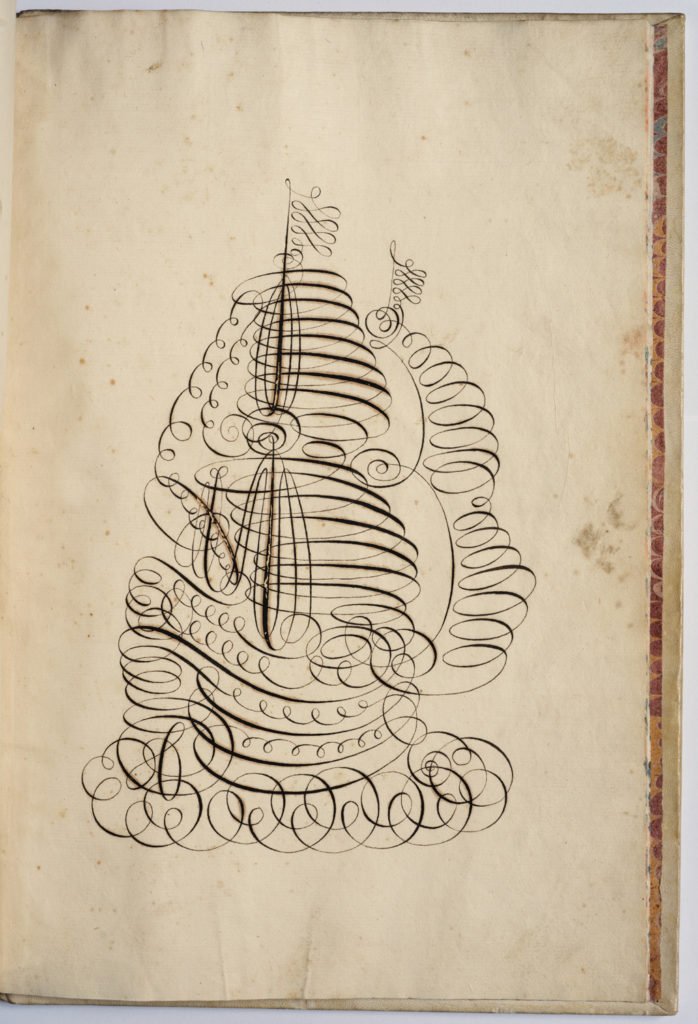

As a young adult, Garzoni lived in Venice for some years; we do not have precise dates for her arrival but it was probably from 1616/17 until 1630 when she moved to Naples. There, she went to a calligraphy school taught by Giacomo Rogni and, during her studies, she produced a book of calligraphy which she called ‘Book of Chancery Cursive Characters’. Art historian Aoife Cosgrove researched Garzoni’s calligraphy book, noting that she was far from the only female calligraphy master active in 17th-century Europe; for example, there was Maria Strick in the Netherlands, and Esther Inglis in England and Scotland.

Garzoni’s book contains 42 individual sheets of calligraphy, ranging from excerpts of religious and historical texts, letters to various recipients, and some combinations of writing and images (like watercolour paintings of animals). One sheet even has a continuous line drawing of a ship (Galleon at Sea, c.1617–1622). Understanding Garzoni’s style in this book helps us to better understand her later works. Cosgrove notes the similarities between the layout of the pages in the calligraphy book and the compositions of Garzoni’s still life paintings later on, explaining that: “each seemed to feature a strong central feature, ornamented with long wispy flourishes and some smaller loci of attention beyond the principal focus.”

Around this time, Garzoni also created several watercolour studies of citrus fruit, for a treatise about the fruit by the scholar and collector Cassiano dal Pozzo (a significant figure in the network of European scientific figures at the time).

Miniaturist in Turin

In the early 1630s, after a brief stay in Naples and then Rome, Garzoni moved to Turin, where Christina of France was eager to employ her as the miniaturist for the court there. One of the artworks she possibly made there was Portrait of Carlo Emanuele I, Duke of Savory (1623-1637). In 1635, Garzoni made the first known portrait miniature of a Black person. This portrait depicts Zaga Christ (c.1616-1638), a self-proclaimed Prince from Ethiopia who converted to Christianity and toured European courts. Zaga Christ may have commissioned this miniature himself as a gift to the French court.

Medici patronage

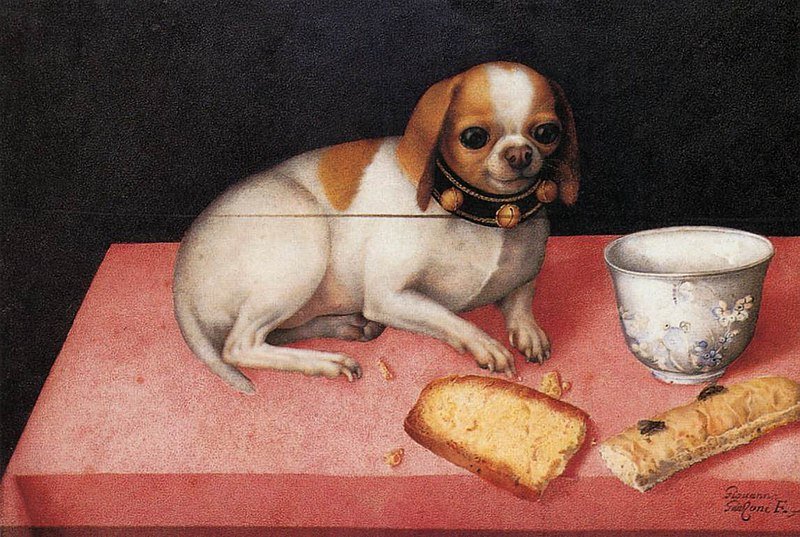

Garzoni left Turin in 1637 and, over the next two decades, apart from a couple of years in Paris, Garzoni moved back and forth between Rome and Florence (she was able to travel freely as long as her brother Mattio acted as her chaperone). During this time, her main patrons were the Medici family. The leading Florentine family were passionate collectors of specimens of flora, fauna, objects and ‘curiosities’ from around the world, ranging from seashells from Central America to Asian porcelain. When the Medici family commissioned artworks from Garzoni, they were - at least in part - making a statement about the global reach of their family, and their access to expensive and rare goods through trade and colonialism. We may recall Garzoni’s words in a letter to a patron years earlier in 1618: “See, O curious eye, epitomised in a brief and small canvas, the greatness of the universe.”

Some of the 20 still-life miniature paintings commissioned by the Medici family between 1650-1662 include:

Later life and legacy

Garzoni finally settled in Rome in 1651 but continued to produce work for the Florentine court. In Rome, Garzoni also went to the Accademia di San Luca, where she took part in events and discussions which aimed to educate, connect and professionalise the painters, sculptors and architects working in Rome. Garzoni died in 1670 in Rome, aged 70 years old, and she left her estate to a church of the Accademia di San Luca.

Today, there are two important manuscript notebooks by Garzoni. One is housed in the rare books library in Washington DC, in which we see a self-portrait when Garzoni was in her old age, and a number of botanical studies. Another notebook, housed in the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, includes flower studies and still life paintings. As more people learn about Garzoni, there will hopefully continue to be more research into her artistic career and into her remarkable artworks. She is a great insight into the relationships of female artists with the courts of the period and an important area of study.

A Hedgehog in a Landscape, 1643-51 (Image: Historical SciArt)

Useful resources on Giovanna Garzoni

Sheila Barker, '"Marvellously gifted": Giovanna Garzoni's first visit to the Medici court', The Burlington Magazine, 160 (2018), pp. 654-659

Zaga Christ Portrait Returns ‘Home’, article in philipmould.com

Aoife Cosgrove, The Art of Writing: Researching Giovanna Garzoni’s Calligraphic Works, blog post for ucdarthistoryma

You may also be interested in watching our video about Garzoni:

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, May 2023)